Some campaigns ask for attention. Late Ho Gaye demands interpretation.

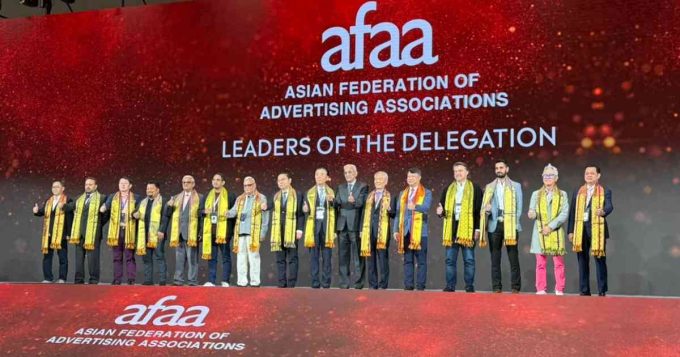

Released on World Education Day, Shehzad Roy’s latest song-cum-awareness campaign, backed by PTCL, Ufone, Telenor, and U Bank, positions itself as music on the surface, but operates more like a cultural audit underneath. It does not dramatise education; it dissects it. And it does so using irony, repetition, and the quiet authority of children speaking for themselves.

This is not nostalgia. It’s a diagnosis.

The Joke That Isn’t a Joke

The opening line, asking parents whether they have secured school admission for their unborn child… lands as comedy. Then it lingers. In Pakistan, the reality makes it impossible to dismiss as exaggeration. This is where the campaign shows its hand early: Late Ho Gaye uses absurdity not for laughter, but for recognition. The humour works because it’s familiar. Too familiar. Roy critiques a system that presents itself as care while normalising competition, sanitising pressure, and wrapping ambition around children.

The song does not accuse. It mirrors.

Power Without Villains

Visually, the campaign avoids easy targets. There’s no single antagonist, no demonised institution. Instead, the film presents power as abstract, oversized, and faceless operating through expectations, deadlines, rankings, and the fear of falling behind. Invisible pressures guide children and parents, not force, because everyone else keeps moving too. This distinction matters. Late Ho Gaye critiques a culture of urgency, not individual failure. The system doesn’t act out of cruelty; it prioritises efficiency. And that’s the problem.

The Aesthetic of Pressure

One of the campaign’s smartest choices is restraint. The set design white rooms, white lights, repetitive exam halls feel intentionally sterile. A relentless, metronomic beat takes over the role of clocks, pressing forward without pause. That beat is doing more work than the lyrics. It turns learning into automation. Progress into muscle memory, not meaning. Even when children speak, rap or protest, the beat pulls them back into order. Only once does the sound pause: when children ask, softly, to simply be born first.

The silence is brief. Authority resumes counting.

Language as Burden, Not Bridge

Perhaps the most quietly devastating critique in Late Ho Gaye is about language.

“Don’t cry in Urdu. Cry in English.” The line lands without a shout. Its matter-of-fact delivery sharpens the impact. The song exposes how systems expect children to perform fluency across multiple languages every day at home, in school, and in tuition while teaching them that only one language holds value. Here, language no longer serves thought; it measures worth. This isn’t a rant against English. It reflects how education systems mistake access for intelligence and how early they impose that confusion.

Childhood, Scheduled Out

The campaign’s emotional core lies in what children ask for not success or freedom, but time. Time for meals, rest, breath, play, and the simple right to exist without constant evaluation. Parents, meanwhile, are shown running endlessly through a maze, chasing better outcomes for their children while slowly losing proximity to them. Screens replace conversation. Tuition replaces family time. Care is outsourced to schedules. The irony is painful: in trying to secure the future, the present is erased.

Speed as a Statement

The direction enforces the message: nothing in Late Ho Gaye ever settles. Avatars shift in seconds, characters flash in and out, the camera lunges forward and pulls back, and AI-generated visuals spiral, fracture, and recombine at breakneck speed. This is not visual excess it’s intention. The relentless pacing reflects a life lived on deadlines, where thought is always chasing the next instruction. Even the music refuses melody, choosing instead a constant, ticking beat that behaves less like rhythm and more like a timer. In a media landscape shaped by reels and shorts, the film understands that urgency itself has become the language and uses it to unsettling effect.

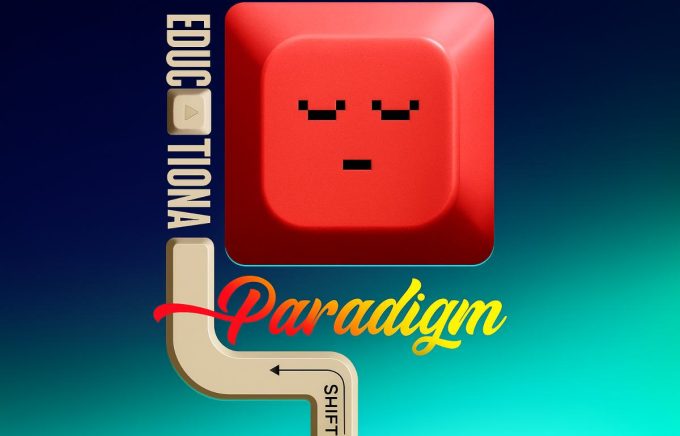

When Design Overwhelms and Why That’s the Point

AI-driven imagery does much of the heavy lifting here: children trapped inside Rubik’s Cube cells, books, bags and lamps towering over bodies, rooms collapsing into spheres, identities looping into puzzles. These metaphors intentionally avoid subtlety. These metaphors don’t hide. They reveal a truth we’ve normalised: tools, materials, grades, and systems tower over the children they should support.

But that choice comes with risk. The same speed and density that grab attention can also blur meaning. That’s the final irony. The film mirrors the cognitive overload it criticises. It rushes you, overstimulates you, and forces you to keep up, until everything fades into off-white silence and the children finally ask to be seen. In that pause, the design stops performing and starts accusing.

Why This Campaign Works

What separates Late Ho Gaye from performative awareness content is credibility. Roy isn’t gesturing from the sidelines. His work with Zindagi Trust provides proof-of-concept education that includes music, chess, creativity, and critical thinking without abandoning structure.

The campaign does not say “imagine better.”

It says “we already know better.”

That shifts the responsibility uncomfortably back to us.

The Promise and the Risk

The campaign ends with a chalkboard message: don’t burden children in the name of education. Educate them well instead. But it’s a clean ending. Maybe too clean.

Here, Late Ho Gaye risks becoming what it critiques: another annual declaration. Another shared video. Another collective nod, before life goes back to the same routines.

Still, the song does its job. First, it slows the beat just enough for us to notice. Then, the real review begins—after the screen goes dark. That’s when parents, educators, institutions, and policymakers must decide: was this just a well-made campaign, or the moment we finally stopped counting 1, 2, 3…and asked why?

Because if nothing changes, then yes! We were not late to admission.

We were late to understanding.