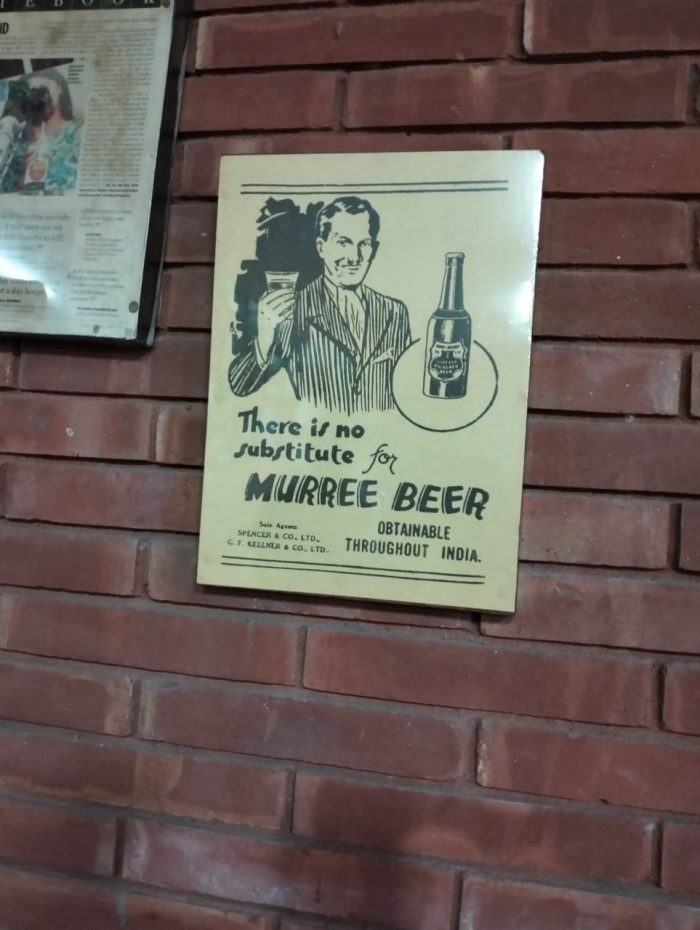

The history of the Murree Brewery dates back to a few years after Britain formally colonized India in 1857, and the emergence of Pakistan was nowhere near. It was established in 1860 by two British engineers, Edward Dyer (the father of the infamous Colonel Reginald Dyer) and Edward Whymper, at Ghora Galli, Murree (the hill station also established by the British in 1851) to slake the thirst of British soldiers and civilian personnel across the subcontinent for alcohol. The brewery, managed by the families of Whymper and Dyer, became one of the first modern breweries in Asia, gaining popularity in army messes across British India as well as becoming one of the largest employers in the region. The company won its first award for product excellence at the Philadelphia Exhibition in 1876.

Between 1885 and 1890, the company established breweries in Rawalpindi and Quetta and acquired interests in Ootacamand or Ooty (South India) and Norailiya (Ceylon) breweries. A distillery was also set up in Rawalpindi, next to the brewery. By 1920s, the brewery in Murree was transferred to Rawalpindi due to water shortage, however, malting continued at Ghora Gali till the 1940s, after which the property was sold out.

Murree’s heyday was World War II (1939-1945), when it produced 1.6 million gallons of beer a year but the business began facing a sharp decline once Partition riots broke out in the region, as a result of which, the historic brewery – constructed in Gothic style architecture – was burnt down. Following Partition, the company also lost a large market of Indian drinkers.

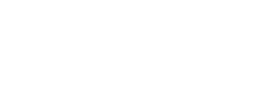

After Independence, the brewery also became an independent company and since then, has been run by the Bhandaras – a prominent Parsi business and political family. Under the Bhandaras, in a new Pakistan, business became brisk again, because even after Independence, the country remained secular (till 1956, when Islamic Republic was added). Hoardings and neon signs of Murree Beer on buildings was a common sight. It was also available on the Wine & Spirits menu of Pakistan International Airlines (which was considered to be one of the 10 best airlines in the world between 1965 and 1979), and until the 70s, the brand was competing with various imported beer and whisky brands in the country. Their target market was the middle-class for whom buying imported alcohol was a luxury.

The fate of the brewery changed forever in 1977 (the only time when it ceased production temporarily), when the (then) Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto enacted prohibition laws and the sale of alcohol and bars were banned in the country, and the brewery was only allowed to sell alcohol to non-Muslim and foreign residents.

Although consumption of alcohol is still prohibited, Pakistan is the only Muslim country in the world to have a functioning brewery, which even today, continues to do roaring business, producing 10 million liters of beer each year, along with hundreds of tons of single malt whisky, vodka and brandy. It is also one of the country’s biggest tax-payers.

From alcohol, Murree also produces a range of non-alcoholic products such as fruity malts, juices, jams, ketchups, vinegars, sauces, as well as Sparkletts (drinking water) under its division named Tops Foods and Beverages.

We interviewed Isphandyar Bhandara, CEO, Murree Brewery, to learn about the company’s history, its evolution over a century and a half, under his grandfather and father, various democratic and military rules, amid political ups and downs; on diversifying into the non-alcoholic category and most importantly, the challenges of running a brewery in a Muslim country.

“Under the British management, my grandfather P.D. Bhandara worked at the brewery as one of the directors. Before this, he worked as a sales agent for a typewriter brand – this is what I have been told by my paternal grandmother,” recalls Isphandyar.

“He died at the age of 62 (in 1961) and at the time of his death, he was already the Chairman of Murree Brewery,” he adds, and points towards a framed news clipping (an obituary) on the wall on his right, which reads:

Mr. P.D. Bhandara breathed his last in Lahore on Tuesday morning. He suffered a coronary thrombosis attack. He was 62. He has been a spokesman for the minority community for a number of years and was a well-known philanthropist. He leaves behind a widow, two sons and a daughter.

At the time of P.D. Bhandara’s death, his eldest son Minocher Bhandara (father of Isphandyar Bhandara) was only 22-years-old and studying at Oxford. The other two children were a girl named Bapsi – a polio-stricken, homeschooled child, who later went on to become the famous Bapsi Sidhwa, “Pakistan’s finest English-Language novelist” (The New York Times), who also taught at several American universities and was conferred with Sitara-e-Imtiaz in 1991 – and a boy named Feroz.

Bapsi was a year younger than Minocher and Feroz was fifteen years younger than Bapsi.

“If at the time of my grandfather’s death, my father was 22, then my uncle would have probably been five or six. There was no chance that he could be considered as heir to the business,” explains Isphandyar.

Since all three children were studying, in the immediate period after P.D. Bhandara’s death, his widow Tehmina Bhandara took over the reins of the business, who according to Isphandyar, was a very strict and reserved woman, “characteristics that dominantly reflected in my father’s disposition,” he says, adding that whatever he knows about the family history has been passed down by his paternal grandmother and not his father because his relationship with his father was very ‘unemotional and practical’.

“Our relationship was not strained but it was different. He was a quiet, reticent man,” says Isphandyar.

Minocher Bhandara took over the family business during the late 60s, when although the company was only producing beer, the business thrived because the beer they produced was also being exported to neighboring countries.

During his tenure, Minocher brought in new machinery from Germany, as well as set up the non-alcoholic division called Tops Juices and Beverages in 1969. In the same year, he also established Murree Glass to produce their own beer bottles, which were earlier procured from Gujrat Glass and Jehlum Glass, small, but very famous pre-Partition factories.

“The reason why my father set up the non-alcoholic division was because he did not want Murree Brewery to be just seen as a sharab-making factory. He wanted to give it a softer and better image. Also, after 1977, following the prohibition, when the brewery was shut overnight, my father realized how important it is to have more streams to the business and not just depend on one.

In the non-alcoholic category, the company started with mango-flavoured juices. According to Isphandyar, at that time, only two companies in Pakistan produced bottled mango juice, Shezan and Murree; Mitchell’s existed but they had not diversified into juices yet.

“Please do remember, that at that time, there were only a few industries in the country and they knew one another. In Rawalpindi, if someone had to find work, there were only two employers, Attock Refinery and Murree Brewery; the third was Pakistan Army. This is how things were during the 70s, the rest was entirely a jungle, with only army houses and the famous Ayub Park,” says Isphandyar.

By 1979, Murree introduced non-alcoholic beers – Malt 79 and Cindy – sold even today with the same name.

(Although the first factory for Tops Juices and Beverages was built in Rawalpindi, the operations were eventually moved to Hattar in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), along with Murree Glass during the early 90s, when Nawaz Sharif, the then Prime Minister gave Hattar an industrial estate status along with tax holiday to businesses for five years.)

Isphandhyar, during his father’s time at Murree, recalls frequently visited the factory on his bicycle. He vividly remembers Pakistan Railways track inside the brewery where empty bogies were filled with beer bottles neatly stacked in jute sacs and sewn on the top to keep them in place. The loaded train would then go to India, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan.

Today, can you imagine exporting or even going to Kabul?” chuckles Isphandyar. “My parents used to go party with friends in Kabul, Tehran and Beirut. It was a different time. Goras frequented Karachi, people went to bars and cabarets, it was a normal thing. Doctors would recommend Murree brandy to patients suffering from cold. Would they do that now? NO.”

After finishing school, he left for the US for further studies, but got homesick and returned only after a year, much to his father’s resentment, and resumed his studies in Islamabad. He confesses that studying was the last thing he was interested in during those years, the priority was always cricket and hanging out with friends. “You see, this is the drawback of having your own business; one lacks ambition. I had no aspirations, because I knew I will be able to sustain myself. Once my father is not around, I will live off this (business),” he says.

Despite the lack of ambition, during his university days, Isphandyar started taking active interest in the business and once done with education, he began worked in Murree’s different departments to learn how they operated, from running machines to store-keeping to looking after the accounts and sales. The process drill continued till 2003/2004, after which he was promoted to the position of director procurement.

“I knew I had to eventually take care of my father’s responsibilities because there was no one else. My sister was married off and my younger brother is mentally-challenged. Moreover, my father’s younger brother and my uncle, Feroz, was never interested in the brewery business. He left for his studies to the US and started his own real estate business there. By the 70s, he became a US citizen. He had 9% shares in the brewery till 2014, after which he sold them to someone outside the family. Today, he is the Malik Riaz of Houston, who made a lot of money buying old rundown properties and renovating them,” explains Isphandyar.

During his training years at the brewery, Murree introduced its famous non-alcoholic beverage ‘Big Apple’ as well as peach and lemon malt drinks, as the company kept looking for opportunities outside the alcohol business.

2008, Minocher Bhandara passed away due to complications resulting from a serious car accident in China. Isphandyar was 35 and married with two sons. He was elected by the board as CEO of the company, and his mother, (Minocher’s widow) Goshi Bhandara became the director.

For Isphandyar, it was not easy getting into his father’s shoes, “especially when you have had an overshadowing father, who though trained me for nine years, maintained his distance and did not make his son his peer.”

Read More: PUTTING ADVERTISING BACK ON THE MAP

But despite Minocher’s stiff exterior, Isphandyar believes when it came to work, his father was a lenient man who overlooked a lot of wrongs; “he let people come in late, forgave them for stealing items etc.” and this happened because most of the time, he was away from the office, travelling.

Apart from Murree, Minoher Bhandara also played an active role in politics and was on Musharraf’s team with a Track II diplomacy with India, due to which he visited India almost every month. “It is because of this that people in the brewery became complacent. When I joined, I put an end to this complacency, and as for the people who could not put up with the pace of production, I showed them the door.”

To bring further efficiency to the brewery’s operations, Isphandyar installed new machinery, both for the alcoholic and non-alcoholic divisions and emphasized on better quality. “Once I became a full-time CEO, with a stick in my hand, things began to change for the better,” he says.

With active, aggressive marketing and frequent advertising, by 2009/2010, the sales began to surge. In 2010/2012, when the US war in Afghanistan was at its peak, the company sold juices without effort. “We sold juices worth USD 2 million to Afghanistan, while in Pakistan, the sales were much more.”

Despite prohibition, the surge in sales for both divisions came on the back of both external and internal factors, including improvement in quality, which was earlier a problem and increase in prices of smuggled beer (which was three to four times the price of Murree). Hence people started opting for local beer.

“All booze comes to Karachi via Dubai, and of late there has been a restriction, which is good for us,” says Isphandyar. He says he is glad that the government realizes that legitimizing Murree and giving more permits, will not just beneficial us, but them as well, as they earn 70% to 80% per bottle that we sell for a dollar. If they ban Murree, the smuggled imported booze will flourish, which will not bring them any revenue.

In terms of sales of alcoholic products, he says the excise department takes decisions. “We are dependent on them. If they give 100 permits, I will issue a hundred trucks, if they issue ten permits, I will issue ten trucks.”

In the alcoholic category, Murree sell seven to eight types of vodkas including the flavoured ones, three types of gin, two types of brandy and two types of rum, along with eight types of beer.

As for selling non-alcoholic products, he says the sky is the limit.

In 2012, Isphandyar also added sparkling water to its non-alcoholic division. Sparkletts – earlier owned by the Hashwanis – is premium quality water from Hattar and Murree and is the first company in Pakistan to introduce water in glass bottles. “It is not as visible in retail as Nestle, but we have more sales in Punjab and KP,” he says and adds that the company will soon be exporting Sparkletts to Saudi Arabian market.

Murree’s non-alcoholic products are exported to US, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Spain, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia.

Today, their non-alcoholic category Tops Fruits and Juices turnover is about PKR 2.5/3 billion a year; the non-alcoholic beer generates the same amount and Sparkletts bring in PKR 700 million annually. Liquor and juices sell equally throughout the year. Beer demand picks up from April through September.

Although all categories are bringing in good money, Isphandyar believes with time, doing business in Pakistan has become harder. According to him, the corruption level has gone up tremendously as well as the costs; the economy is screwed up, thanks to the PTI government. “There is so much talk on ending corruption that all bureaucrats, linemen, civil servants, inspectors are scared of getting caught, hence, they have increased their rishwat rates. This is because the more you talk against something, the more people will do it! Imran Khan beat the drum so much now that my work is stuck. All businessmen are affected by this, it’s not just me,” he says.

Talking about his plans for Murree, Isphandyar believes it is important to stay abreast with trends as without innovation and change, any industry will die. As for growth in sales, he says as long as religious reactionaries do not get control of the country, the brewery’s future is bright.

As for his successor, Isphandyar says although he wishes to see one of his sons take over Murree Brewery as CEO since it is a legacy business, he will not enforce it. “Even if they do not want to join the company, it is important for them to find their true calling, because if they want a comfortable life, they will have to work. I am not leaving them unlimited amounts of gold.”

He says since Murree Brewery is a public limited company, with an independent board, the company will find a CEO. It will not die out or suspend operations.

“If my sons join, it is good, if not, not a problem. The company will make arrangements.”