A decent election campaign lies at the heart of democracy. Financing that decent election campaign, as such, lies at the heart of the heart of democracy. That being so, finding

political space on the landscape is directly proportional to one’s capacity to raise and manage funds professionally. At the policy level, however, it is the system that has to ensure a level playing field for all the entities in the ring in terms of ways and means to raise funds and to control the ultra-enthusiasts who may go a tad too far in search of that elusive dollar.

To ward off the risk of policies that sway in favour of certain influentials/lobbies, undermining the public interest, it is equally important to put in place an effective tracing and tracking mechanism of private election funds and equip the regulator to effectively scrutinize the finances of parties and candidates. The current legal framework that regulates campaign funds in Pakistan is rather archaic. The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) lacks the capacity to audit accounts effectively, identify violators and proceed against them under the law. The framework itself is said to

be weak and needs to be amended to correspond and respond to the current and emerging realities.

Even a cursory look at the conduct of contestants, up and down the country during the last three polls, irrespective of the party, they disregarded fiscal rules and violated spending limits set by the ECP. Under the law, all candidates are obligated to open a dedicated election account and declare the account number at the time of filing the nomination papers. The law requires them to channel all election-related expenses solely through this account. However, it seems that not many people take these rules seriously, although many do submit the balance sheet of the dedicated account, along with payment vouchers, to the ECP.

An intelligent estimate puts a price tag of Rs440bn on General Elections 2018. It included all spending incurred by the government, the candidates, the political parties, and the donors. The election spending five years back was 10 percent higher than the total cost of Rs400bn in 2013. Many watchers found these estimates conservative. When asked to comment on the published estimates of spending in the past three election cycles, the head of the ECP’s finance cell declined to provide a quote and pointed out that the spending estimates were arbitrary observations lacking empirical evidence. However, he did acknowledge that election expenditure by participating candidates has undeniably exceeded legal limits.

According to the ECP hierarchy, the balance of account submitted by the candidates have not been properly audited. “The regulator lacks the capacity to carry out the (required) massive audit exercise within the permissible time period. We are trying to improve both fiscal rules and their implementation. A separate finance cell has been set up for the purpose in the ECP,” Qurat ul Ain Fatima, the ECP spokesperson, told this scribe over the phone from Islamabad recently. The Election Act 2017 revised the spending limit of candidates from earlier Rs1M and Rs1.5M for provincial and National Assembly seat

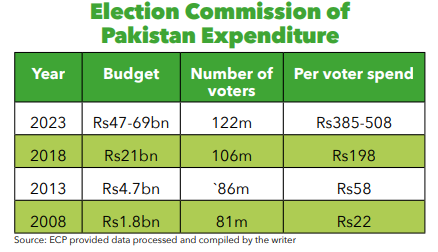

aspirants, respectively, to Rs3M and Rs4M. The Election Commission’s own spending per voter has increased several hundred times over the past 15 years. From Rs22 in 2008, it hit Rs198 in 2018 and is expected to clock somewhere in the band of Rs385-508 in the General Elections 2023, scheduled to be held later this year.

See table for details:

A former chief election commissioner was not surprised at the hike in the ECP’s budget. “You must factor in the compound inflation over the last decade-and-a-half and the number of by-elections since July last year. In 2008 a roti (bread) cost two rupees, and a dollar cost 60 rupees. Today, low-weight bread costs Rs20, and one dollar equals over Rs300”. Chief Election Commissioner Sikandar Sultan Raja was approached for comments on the subject over the phone. He was busy but shared the contact details of the officers concerned to provide the required information. A senior officer of the finance cell did mention some legal lacunas, but not what was stopping the ECP from improving the legal framework to make it more relevant and effective.

Regrettably, the fiscal aspect of elections in Pakistan has not been subjected to systematic research and analysis by any independent or governmental entity. Two well-known organizations involved in electoral matters, namely the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT) and the Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN), were unable to contribute significantly to the debate, aside from sharing the relevant sections of the Election Act that address election financing. They did agree that the subject merits more attention as it affects the quality of democracy.

Surprisingly, despite the volume of capital involved, no one in the government or outside has done an exercise to realistically assess the minimum budget necessary to put up a decent electoral campaign by a candidate in rural and urban constituencies of the four provinces. The research on the subject based on the market surveys and interviews of contractors and assembly seat aspirants showed that close to 80 percent of transactions during the campaign are cash-based, leaving no money trail. Key candidates on hotly contested seats, in particular, often spend more than what their financial standing justifies, observations of past elections indicate.

The need for money in elections means that people who wish to enter the race must ensure easy access to ready cash. I know that candidates start hoarding cash early in an election year. Former ministers/advisors in the race start calling favours back. The unearned liquid assets (bribes or proceeds of other illegal side business) are pooled. Rich lobbies and even mafias are approached through contacts for patronage”, a source familiar with the election affairs in Karachi commented.

Majyd Aziz, an industrialist from Karachi,h said many prominent seths (businessmen) often support promising candidates irrespective of the party. “It’s too risky to put all eggs in one basket. Seasoned tycoons supported two or more contestants of different parties in

the same constituency.”

Another business leader said the influential business lobbies of cement, auto, pharma, traders, realtors, bankers, brokers, etc., pick a party to back instead of candidates. “There is nothing in writing, but it’s a quid pro quo deal. Similar to any investment, one

allocates resources today with the expectation of future dividends. The decision is reached by exploring the top-tier leaders of major political parties,” he confided.

“Often, personal capital is exhausted even before the actual electoral race begins. Cultivating leaders is an expensive endeavor, especially for candidates from rural constituencies. In addition to paying the party for a ticket, a team of contractors needs to be hired to handle various tasks such as providing laborers, transportation, advertising, social media campaigns, election office and camp spaces, printing, food, sound systems in offices and floats, and so on.” These days no one is ready to trust and better service providers like to be paid in advance, at least partially at the time of the deal”, a member provincial assembly shared but did not agree to go on record.

Multiple politicians asked about the source of campaign funding were evasive. Some said they had to sell the property to raise resources to get into the ring. Contacts in the real estate market have confirmed a temporary decline in property prices near general elections, which is attributed to the sudden influx of an unusually high number of sellers in the market. Individuals involved in auto rentals have mentioned that new vehicles are introduced, and their rental rates are adjusted based on their popularity. “There is too much uncertainty this year; people in the business are waiting in the wings for the election date announcement to put their business plan in action to make the most of a once-in-five-year opportunity”, said a car dealer from Lahore.

Speaking about the source of massive funding, most people approached were not clear though they hinted at the surfacing of hidden wealth during elections. “Millions, if not more, change hands. Most transactions, big and small, are in cash without proper vouchers and receipts. There might be some shady characters active, but no one can survive in the market with a tainted reputation. Normally businesses related to electioneering are trustworthy and honour deals they agree to even if verbally”, said a contractor who provides workmen for putting up banners and manning election camps.

“It has less to do with the political leaning and more with the timely payment”, a Pakistan Peoples’ Party voter sitting at Pakistan Tehreek e Insaaf camp at Gizri said. “It’s a part-time job that you do to earn a little extra. Yes, I attend PPP rallies in Layari and will cast my ballot for Bilawal Bhutto, but it doesn’t mean that I will forego the job opportunity”, a Baloch youth told the writer during an informal survey before the 2018 elections.

“Money can only come from places where it exists and is stashed. The middle and poor families who can barely cover their family needs can’t be expected to fund the political ambitions of wannabes”, remarked a college professor. “I have colleagues who support causes and may be ideological ones give some petty donations to their comrades, but can they actually make a significant donation to build a winning campaign? I seriously doubt that. All candidates need rich patrons for a decent try at elections”, he added.

Currently, there is no cap on the spending by political parties though they are required to justify their source of funds that can only be raised from individual donations by Pakistanis. The corporate lobbyists, when they wish to support a party, often pick hefty bills of election activities via some middlemen, anecdotal evidence suggests. Demonizing electioneering by competing political parties and aspirants who wish to represent people in either of the two tiers of the legislative assembly may be fashionable but counterproductive. Money is required to put the message across to the public. It provides people the basis to make an informed choice at the ballot.

Democracy in Pakistan is new, barely 15 years old. Never before in 75 years of the nation’s history did power got transferred or extended after a fresh lease of mandate – at the designated five-year interval.

“The bond of economics and politics is as natural as the relationship between development and human survival. Often the market and democracy progress in unison. Money is vital to communicate with citizens/voters, be it a political party or a candidate aspiring to represent people in a legislative assembly”, commented a keen watcher.

“A good political campaign not only brightens the chances of a party/candidate in an election, the flow of information empowers people to compare contestants and chose the one they would like to trust with legislative power,” he concluded.