In a world where there is peace amongst the many nations, where there is no poverty, where no one has to work, where there are no lies, where there are no people being enslaved, where there is no disease, where there are no power outages, fuel hikes, crumbling economies or fluctuating governments – there is the absolute knowledge of creation. A place such as that, the perfect utopia is a thing of the imagination. An ideal that emerges perhaps only when one is tired (or bored) of the world that surrounds us and wonders about the inanity of all the senselessness we are surrounded by. One starts creating fantasies that lead to or form the idea of a utopic existence where everything is in an existential or empirically designed harmony. Thus also, arrives the idea and the need to educate, to inform and to extend knowledge through exploration and eventually, experimentation.

When we talk about design or the ideas that it can represent, we tend to mostly think of it as only to be created towards addressing functionality. If it’s not serving to “solve” something it becomes difficult to call it design and it starts gradually falling into the realm of “art”.

This is a fundamental disagreement I have had with some of my artistically-inclined peers during my time spent teaching. Where my understanding of design or art for that matter, starts to overlap their understanding of design or art, things become nebulous and the perfectly isolated utopia that’s been built around either of the disciplines starts to crumble into abstraction. Disciplines become fluid, and to give it a visual metaphor, it becomes like liquid blue, purple or green of one viscosity being mixed with a red, yellow or pink of another viscosity creating a strange marbling visible in a million new forms and colors. It is an input, with the intent of creating an output without really knowing what the result will be. And the resulting creation is an oddly harmonic cacophony of forms and colors. If you haven’t, look-up “acrylic pouring” on YouTube, and you will see what I mean. The thing I find most interesting about the whole process is that no matter what, the end result always – literally always – looks amazing. The best part is watching the paint as it moves, it slides over the surface, mixing, blending and always creating something unforeseen. Watch it, it’s beautiful.

As you watch, you will think – hey, even I could do it! And believe me, you can. It really is that easy to pull-off. But it will be very different when you do it. The paint will always move and mix in interesting ways but it will not always work the way you would like it to. Then, you will start to work towards making it into something that you want and eventually you will start making it work for you. And that my friend, will be your glimpse into your personal functional or nonfunctional utopia.

The question that pops up then, is how do you incorporate the idea of that formless becoming into the minds of students? Where their mind becomes unconcerned with the function of a utopic state but ends up focusing on nothing but boundless creation. Utopia is not necessary, creation is.

The way design is being presently being taught in Pakistan is for the most part limited to its having students make pretty pictures that must always serve a purpose. Nothing wrong with that, sure, everything must have a purpose. But to limit it to being a problem and then coming up with solutions, in my mind this approach reduces the discipline into limited functionality and creates a distinct division between expression and the lack of it thereof. Where art becomes humanely expressive, and design becomes limited to catering to audiences and creating facilitative experiences only, which are essentially inexpressive and detached from emotion, we like to call it “user experience”. The boundary between the disciplines of design and art becomes stark and does not allow for the disciplines to converse, placing art on an imaginary pedestal that not only does not exist but is also exclusionary by nature. The equation has no alchemy and so, limited reason to either experiment or evolve. Design must always serve, and art does not have to. A hierarchic and dated notion, as far as I am concerned.

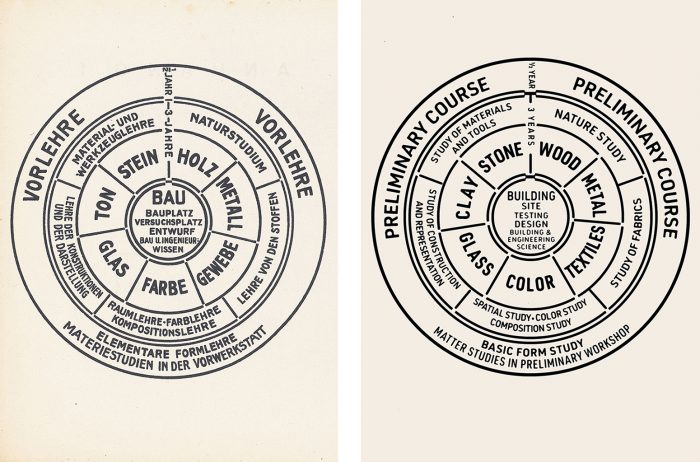

The diagram above was designed for the Bauhaus by Walter Gropius in 1922 and illustrates the principles and curriculum for teaching and learning. This can serve as both a reminder and parallel to the design of a curriculum that develops a holistic understanding of design (eventually, art) and its application. Interestingly enough, nowhere does it stress functionality or the provision of solutions on a structural level. It would be impossible to detail all the intricacies that come into play over the course of teaching and will have multiple variables determining the eventual product. But the illustration remains devoid of bias towards any discipline and all the elements are housed within a circular mandala that encourages the transmutation of the disciple or student into something utopic.

In an oddly opposing manner, the resulting work from this model laid the foundation for what we now tend to associate towards form and function – albeit in isolation – while overlooking the fact that function and the lack of it thereof are not the objectives of education, but the nullification of them. The moment any binding is applied to the creation and dissemination of knowledge, it stops evolving. And we start visual dystopias lacking context.

Read More: Bionic Films Rebrands

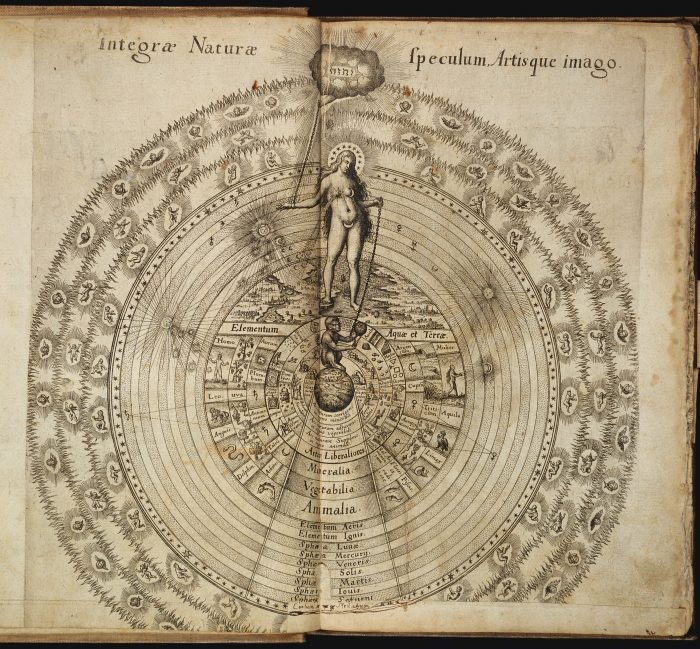

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. Alchemy, in the many forms that it is practiced, is meant to create transmutative experiences whether they are on a philosophical or physical level.

The illustration above, although much more complex than the former, does have some fascinating parallels. One, it has its origins in alchemy and alludes to transcendence. Second, it includes the study of elements and materials – concepts essential to the transmutative process. Third, it establishes an idea of stages that become progressively concentric. And last but perhaps most importantly; it is a designed visualization of the process that can enact the philosophy embedded at its core.

Both diagrams are vastly different but essentially work on the principle of developing a holistic understanding of the elements within the student.

The process of learning and implementing knowledge is obviously much more complex than the simplifications I have posed above. But it is ultimately governed by the systems being practiced by instructors. Who, in our case, are either limited by their fear of not being able to cater to the needs of the industry or by the illusions of their own limits.

Over the course of my teaching in Pakistan, I came to realize that the education landscape of design focuses on transformation and function more than creating opportunities within the learners to evolve and experiment.

Design does not always need a client, it does not need an audience and more than anything, it does not always need to have any function. It can sometimes, just be. And that is where it starts gaining an expression of influence that is not bound by an externalized need that must always be justified, but by the visualization of an expression that can be as abstract as the mind that produced it.

In the end, you may agree or disagree with my dismissal of the fact that design is limited to creating usable and functional utopias only. Yet the reality however remains that the teaching of design must not be limited to what it is, but what it can potentially be.