Do you wonder if your choice about something was driven by listening to other people’s opinions, reading something, or following a general perception? Like by now, you should realize that the only reason you bought the clothes of a certain brand was because you were hearing a positive narrative about it.

Similarly, the vote our ancestors used to cast was based on several carefully plotted stories, which are now known as political narratives or propaganda. Don’t worry; we probably did the same. We think that political institutions aren’t that smart, but truth be told, they were evil geniuses of the advertising world. From knowing their audience to the great use of the mass media tools available, it takes a lot of effort to build a political narrative that also shapes the cost of a country’s future.

If we take a look back, there have been many regime changes in Pakistan. But some stand out as they shaped the history of this country with political narratives that shooked the nation from Balochistan to Khyber. Just keep noting how these campaigns had great elements of advertising and clever use of mass media.

Ayub Khan’s Well-Designed Propaganda Against Fatima Jinnah

In 1965, one of the most dramatic encounters occurred in Pakistan’s political landscape. Ayub Khan had to face the challenge of competing against Madar-e-Millat Fatimah Jinnah. The rank and prestige held by the sister of Quadi-e-Azam should have been enough to make her the first woman to lead Pakistan. But when someone has the power to shape a narrative and use mass media to his benefit, they can change the situation quite easily. The same was the case with Ayub Khan, who held the position of President of Pakistan and was clever enough to design a narrative-based political campaign.

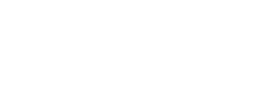

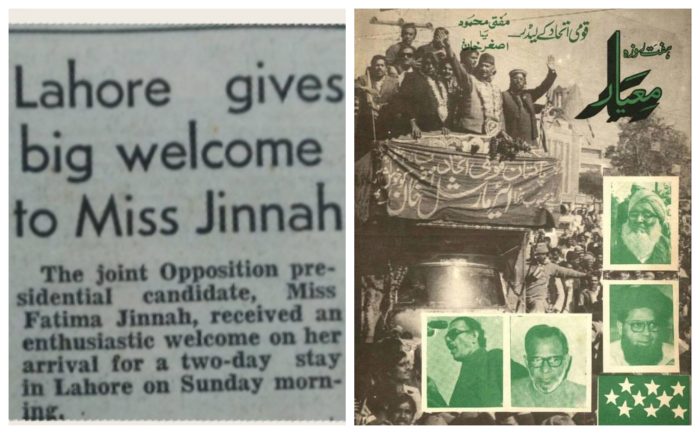

Fatima Jinnah came out of her long retirement from politics with the stance of competing against dictatorship. She had an honourable image among the masses. Several newspapers commented on her campaign by stating that she was preaching the motto of Quaid-e-Azam. Her warm welcome in Lahore also got coverage. However, there was stronger propaganda in her way that proved lethal.

The mass media, aka newspapers because it was the largest medium, played a significant role in promoting Ayub’s narrative. Some commented that choosing Fatima Jinnah because she’s the sister of Quaid-e-Azam was not a wise decision. Few stated that people should not opt for emotionalism. One journalist wrote that India would want Fatima Jinnah as president.

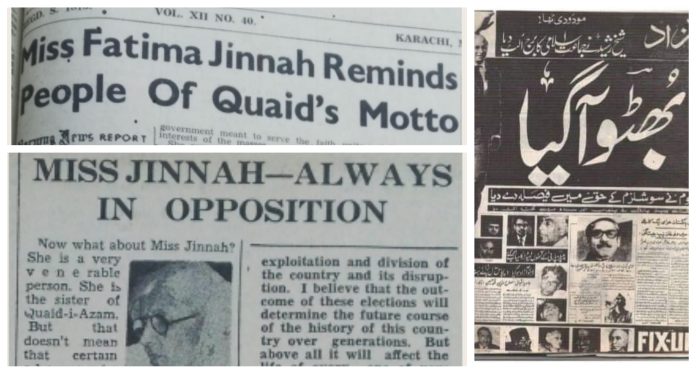

But the greatest of all narratives was when the media said that ‘women cannot be a head of a Muslim state’. What can be more fatal than playing the religion card at your convenience?

Some of the headlines of that era read:

- “Woman cannot be head of state.”

- “Islam debars females from becoming head of state.”

- “Woman cannot seek election as head of state.”

Hence, no counter-narrative could have eradicated the effect of Ayub’s campaign. Despite a popular newspaper Nawa-e-Waqt providing good coverage of Fatima Jinnah, Ayub easily marched to the president’s seat.

This election was the first instance of using the weaknesses of the opponent to your advantage with the help of mass media tools. However, a much bigger and massive scale slogan gave a new direction to political advertising & narratives.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s Ultimate Slogan

By the late ’60s, a new narrative came to light. It claimed that the resources of Pakistan are being held by a group of elite-class people. This became the base of an ever-green slogan that was promoted by mass media and social groups. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto gave the most popular advertising slogan of all time, “Roti Kapra Aur Makaan”.

The effects of a dictatorship rule caused economic challenges, and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto took the opportunity to become the leader of Mazdoor (worker class). He emerged as a person who advocate for people’s rights.

But it took more than just a slogan for him to become a populist leader. When the war of 1965 ended as a result of the ceasefire, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came to the limelight by claiming that Pakistan could have won the war if Ayub Khan hadn’t agreed to the ceasefire. The country was already in emotional distress and anger. The narrative resonated with them, and they started to accept Bhutto as their spokesperson. A little support from mass media helped in image projection. By 1970, he had all the narrative power to form a government that had massive scale popularity.

Coming back to the popular slogan, the Roti Kapda Aur Makaan tagline had all elements of effective marketing. People were in distress of multiple wars, economic disputes, and high unemployment rates connected the masses with this narrative. The media used to give great coverage to Bhutto’s speech which further strengthened him. One such example is his speech in which he said the iconic words:

Yeh qaum eik azeem qaum banayge, yeh qaum dunya ka loha banayge. Qabool hai apko? Tau khidmat karo gay, mehnat karo gay, laro gay, maro gay, aur jado jehad karo gay, eeman say karo gay, Allah ki kasam karo gay?

The part of the speech is preserved through electronic media. An interesting insight is that the people responded to every call of Bhutto during this speech.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had a secular roadmap of government. When he won the elections, the news headlines read, “Pakistan accepted secularism”.

Now a stronger story building was needed to oust him. What can be stronger than a religious alliance and its narratives?

1976-1988: From Forming Narrative to Caging Media

During 1976-1977 a special group was formed by the name Pakistan National Alliance that consisted of right-wing parties. They all joined hands to create a series of perceptions that would lead to the end of the Bhutto regime.

The PNA started to propagate that Pakistan needs Shariah laws. They build their narrative against the secular approach of Bhutto by narrating that alcoholism and other activities have escalated during his rule.

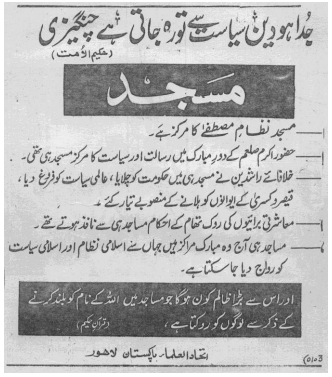

Remember a popular line “Juda ho deen se siyasat to reh jati ha Changaizi”? This slogan was created by the PNA and used the print medium for its promotion.

Though Bhutto was ousted through a military coup, the narrative built by PNA became the base of government that ran from 1978 to 1988. These ten years were the time when electronic media, print media, and radio were forced to promote a narrative of government. From implying the press gagging act of 1857 to applying the motion picture ordinance in 1979, the media hardly had room to give their unbiased opinion.

The follow-up years had somewhat similar narratives that mainly roamed around anti-American threads. Moreover, after the 9/11 tragedy, it gained more strength mainly because the Pakistani community and Muslims got labelled as terrorists.

A major change in the use of media tools to design new narratives occurred after 2013. Social media got popular across Pakistan, and the era of digitisation was evident. Since youth got more connected with social media and digital tools, they became the new target audience. The whole situation was capitalised immensely well by one political party and its leader, who made Pakistan cricket world cup champions in 1992.

Social Media War; Imran Khan Is a Case Study

Everyone can recall the term ‘Keyboard warriors’. This phrase became popular because former prime minister Imran Khan used the mediums like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and other digital platforms to build his narrative of ‘Naya Pakistan’.

He had the perfect plot to design the campaign. His target audience was teenagers who did not resonate with the political leaders their parents followed. The primary medium, cleverly chosen, was social media because conventional media had more restrictions, and social assets gave better room for brand building.

The elections of 2018 are where PTI re-defined the use of social media. They had 150 million mobile phone users. Around 57 million of them had 3G/4G facilities, and 64% of the population was youth. Public figures, actors, and social media influencers played a major role in uplifting the campaigns of Imran Khan. One positive Instagram story on PTI had more power than several ads running on conventional media.

The campaigning of PTI achieved fruitful results on all fronts; From trending on Twitter to podcasts in favour of PTI to targeting opposition members on social media, they left no stone unturned.

Now, the question is how effective will be narratives and propaganda in the future. Will the nation always fall prey to carefully seeded stories or focus on electing members on merit? The situation is blurry because the above events clearly tell that the nation wants a ‘new product’ after every few years.